September was a long time ago. Since then, our world has been changed forever by the Simchat Torah massacre and the war that followed. It was 24 hours that turned our world upside down. For those of us living in a wine bubble, we were forced to face an unpalatable truth: wine could not be more unimportant. Suddenly topical wine articles were no longer required. The wine writer was redundant. So, I have waited until now to write about something very exciting that happened before October 7th.

It is a story that connects our ancient history with modern Start-Up Israel. And it is wine based. How many other products were as important to the ancient Israelites as modern Israelis? Furthermore, in today’s uncertainty, the vineyard represents life and continuity. The humble grape was eaten by some and used to make wine that permeated every Jewish lifetime ceremony by others, but in this instance, we are talking not talking about vineyards, vines or grapes, but more about seeds. When did you last have a conversation about grape pips?

Think of the hundreds of times you ate the fleshy part of a grape, separated the grape pips with your tongue before spitting them out. Did you ever stop to think what happened to those pips? Did any of them have a name, or maybe a history? A grape pip is something so small that it is difficult even to pick one up between thumb and forefinger. Well, two grape pips have recently become pretty famous in wine circles.

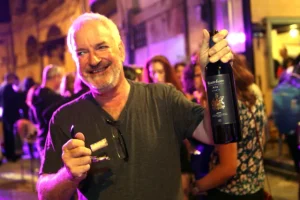

Credit: Ron Peled

Professor Guy Bar-Oz of Haifa University is the person responsible for the research. He is a bio-archaeologist at the School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures. He is dynamic, charismatic and fascinating to listen to. His work, and to be more specific, his findings, are sensational and electrified the wine world. He has been involved in ongoing ground breaking research regarding the history of the wine industry in the Negev Desert. Excavations had already given proof of a flourishing wine industry in the Byzantine and early Arab period, especially at sites like Shivta, Halutza, Nitzana and Avdat. However, Professor Bar-Oz was able to scratch deeper. For instance, by going through the ancient trash, he and his colleagues discovered that the thriving Byzantine wine industry came to an end because of plague, earthquake and economic depression, and not as previously thought, because of the Muslim prohibition of alcohol. That is a over simplification of some incredibly complex research, but you get the idea. There is some amazing bio-archaeological work going on unlocking the secrets of the past.

Credit: Danna avidan

Back to those grapes. A number of grape pips were found in an enclosed stone room in the ruins of Avdat in the heart of the Negev Desert. Now, Avdat is a National Park with Nabatean, Roman and Byzantine roots. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Its large well-preserved wine presses titillate our imagination. Here they made wine in very large quantities. Avdat connected the spice route between Petra and Gaza. Presumably a pip thrown in the trash or spat on the ground would be a loner. However grape pips found in groups together, are more likely to have been cultivated or used for winemaking. Most of the pips are bashful and shy and give scant information, especially after hundreds of years. The arbitrary results of years of research with numerous pip samples, only hit the jackpot occasionally. Very occasionally. They remind me of the genie in Aladdin, stuck in the oil lamp for an eternity. We are doomed never know his story until, hey presto, the genie escapes from his prison. A pip hidden from the world for centuries is not certain to yield its secrets, but two of them decided to become famous.

Under the painstaking work of Dr. Meirav Meiri of Tel Aviv University and researchers from the Israel Antiquities Authority, these two grape pips sang. Meiri is curator of Bio-archaeology and Head of the Animal and Plant Ancient DNA at the Steinhardt Museum in Tel Aviv. Wearing something akin to space suits to avoid contamination, the researchers went about their delicate work with no certainty of success. The pips were cut in half. One half went for DNA tasting and the other for carbon dating. Again, this is grossly simplifying a very complicated process. Two of them though, yielded enough information to electrify the wine world.

Credit: Devorin media

Now, we know that Zion Winery founded by the Shor family in 1848, used the Holy Land indigenous varieties to make wine. They had long term agreements with the same Arab grower in Hebron for generations. They used the same indigenous grapes of the Holy Land, that now have so caused so much interest. These grapes were chosen not for their special qualities, but because they were available. For sweet wine they did not need anything out of the ordinary. In any case, the wine in those days was referred to by its place of origin, Hebron, rather than being named after the variety. So, the local grape varieties were present but anonymous! These days, they have made a comeback and prompt a great deal of interest. However, the possibilities and new interest only came to light when Cremisan Winery, owned by the monastery, decided to focus on local varieties from 2008. They employed the services of Italian Riccardo Cotarella, one of the most famous winemaking consultants worldwide. Furthermore, their current general manager and winemaker, Fadio Batarseh, studied in Italy and Hebron University and based his thesis on local Palestinian varieties. When in a tasting of Israeli white wines by Jancis Robinson MW, the world’s most famous wine critic, the Cremisan Hamdani Jandali came in first, suddenly the fact that there were some interesting local varieties was no longer a secret.

Then totally separately, Dr. Shibi Drori, winemaker of Gvaot Winery and agriculture & oenology research co-ordinator at Ariel University, began his research on indigenous varieties. He and his colleagues scoured the country from its top to its tail, and decided to catalogue all the varieties they could find. They identified over 120 local varieties, of which twenty show wine potential. The research is ongoing. In 2014 Recanati Winery, with the creative input of winemaker Ido Lewinsohn, soon to be a Master of Wine, made their first Marawi, a white wine. It made a noise and not just in wine circles. A joint venture between a local Holy Land variety, Palestinian grower, Jewish winemaker and Israeli winery made it a unique collaboration. The world’s press talked in excited tones about the wines King David and Jesus drank, but this was more the poetic license of dreamers, rather than being with a smidgeon of concrete scientific evidence. Maybe you should not spoil a good story by the truth! Also, the truth is that most of the local varieties used to make wine so far, came from the Hebron region, under the auspices of the Palestinian Authority.

Dabouki, grown heavily in the Hebron area, was the local variety most prolific in the State of Israel. The name means sticky sweet. It was particularly popular pre-state, being planted in the Mount Carmel and Judean coastal plain area and was popular until seedless grapes became commercially available. The large wineries often used their Dabouki for distilling into brandy, for which there was then a big following, but it was mainly popular as a succulent table grape…until Cremisan gave it new life as a wine grape.

Back to those desert pips of Avdat. They really did reveal valuable information. Firstly, they were dated to be approximately from 900 CE. This was during the early Muslim period, but Monasteries and Christian enclaves continued to make wine, and they would have done so at Avdat too. Secondly, and this is incredible, they were found to correspond to varieties known today. One matches a red variety known as Syriki. Could it possibly derive from the word ‘Sorek’ which has wine connotations or maybe, ‘Syria’, a geographical connection? Anyway, this variety is also known in Greece (in particular Crete) and Lebanon (where it is called Asswad Karech). The other matched a local white variety we call Be’er. This was a wild vine discovered by a well (be’er in Hebrew) at Palmachim, in the southern coastal plain. Barkan Winery took cuttings, propagated them and planted the vines to produce a wine. Well, the desert Be’er was planted at Avdat over 1,100 years ago. Could it have been used to make the famous Gaza sweet white wine that was exported throughout the Mediterranean? They were shipped in the recognizable torpedo shaped Gazan amphorae. This is educated conjecture, trying to connect the dots, but who knows? What we do know is that it is the oldest white grape pip to be identified; the scientific journals, and wine magazines like the Wine Spectator and Decanter, were quick to bring the news to interested ears around the world.

In those days wines were referred to by the port from where they were exported or the style of wine, rather than the grape variety. So, Jewish literature in the Bible and Talmud does not talk about grape varieties. One of my constant beefs is that we research our sliver of a country like an island. If we could share our research with Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Cyprus, who knows what secrets could be revealed? After all, under the Ottoman Empire, there were no borders. It is highly unlikely the Dabouki variety for example, was confined just to the region that would later become Israel.

Credit: David silverman

Anyway, in the autumn I found myself travelling to Avdat to witness the ceremonial planting of a vineyard, not of Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, but of ancient grape varieties, Be’er, Syriki and Dabouki. After 1,000 years they returned to Avdat! The idea was to plant an educational vineyard to recreate the lost varieties of the Negev Highlands. Prof. Bar-Oz received a grant from the ERC to replant these ancient varieties so the research may be continued. Analyzing the molecular signatures and genetics of these varieties could give clues of what is needed to survive in an arid climate.

The Israel Nature and Parks Authority, University of Haifa, Israel Antiquities Authority, Merage Israel Foundation and Ramat Negev Regional Council hosted the moving event. There I was pleased to see Dr. Meirav Meiri again. We had met previously. She is so quiet and modest, but obviously brilliant. I find her research breathtaking.

Mostly I was pleased and honored to meet with Professor Bar-Oz. He gave a fascinating speech. He is a force of nature. Most academic researchers I meet are dry, scientific types and not great communicators. They often have the passion of a fossil and speak in an obscure language of the researcher that is difficult to follow. Bar-Oz defies the norm. He is bursting with information and overflowing with passion for the subject. I wish for all students and tourists, that they will find teachers of history and tour guides with an ounce of his knowledge and a sprinkling of his stardust ability to explain, enthuse and bring the ancient to life. We will be following his research carefully and with great attention, and I look forward to when I next have the opportunity to hear him speak again.

The Negev makes up over half the country. It is our largest wine region in area, but the smallest in the number of vineyards. The first desert vineyards in our times were planted by Carmel at Ramat Arad in 1988, followed by Tishbi at Sde Boker, Barkan at Mitzpe Ramon, Carmey Avdat, and Ramat Negev Winery at Kadesh Barnea in the 1990s. The first desert wineries founded were Kadesh Barnea in 1997, Sede Boker in 1999 and Yatir in 2000. Now there are no less than forty wineries from the northern Negev to Eilat. These make up the ‘Negev Wine Club’ so magnificently encouraged and supported by the Merage Foundation. Negev wineries are generally small and idiosyncratic, making wines that are highly individual, characterful and authentic. The scene is not blemished by large or medium sized commercial wineries in the area. It takes a special sort of character to settle in the desert, plant vines and grow a vineyard and make wine. So, the characters one meets on the Negev wine route are not replicated elsewhere. The most high-profile Negev wines are made by wineries such Nana, Midbar, Pinto, Ramat Negev and Yatir. However, the real interest is knocking on a cellar door and finding someone totally original behind it, producing something unique. Remember wine is a product of a person and a place. That is the magic that is particularly apparent in the Negev.

The Negev Desert is certainly a fascinating place, well worth exploring. For tourists, this is the best place for agri-tourism in the country. Find a winery you want to visit, and around it will be places to stay, eat, visit and party in the unique way that only the desert offers. For wine lovers, including Israelis, the Negev is relatively new as a wine destination and it still seen as quite exotic. Sometimes the curiosity can propel one to drive south, just to see what a desert vineyard looks like and appreciate how a desert wine tastes. Quite apart from anything else, since October 7th, Israeli wineries need support and none more so than in the Western Negev. As for winemakers from all over the world, the Negev is a must. The research and development being undertaken by academics, growers and winemakers provides hidden information for those seeking solutions and creative ideas to cope with the fears of global warming.

When I first came to Israel in 1989, there were wines called Avdat produced by Carmel. As a newbie, I asked what was Avdat? I was told “Ah, it is a place where they used to make wine.” Of course, I was later to discover what an important archaeological site Avdat is and how significant it was in our wine story. After the ritual, celebratory planting of this new vineyard with ancient varieties, we walked up the slope to the Roman villa of Avdat, where we were given a tasting of Negev wines by the Desert Wine Bar of Miztpe Ramon. They list as many desert wines as anywhere in the world I should think. After tasting the wines, I quietly wandered off with Zvi Remek of Sde Boker Winery to the far side of the archaeological site, to go and see one of the ancient wine presses. Standing next the wine press, I was exhilarated to see that we were overlooking a large vineyard of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon; a defiant patch of green, surrounded by the beige, browns and yellows of the sandy desert. Here was a 1,500 year old wine press, an established modern vineyard and a new vineyard reeking of history, all in close proximity. That in a nutshell is the story here. Soon they will be making Avdat wine again from varieties that grew there so long ago. Israel is making the desert bloom with vineyards and the ancient world has sprung back into life.

Adam Montefiore is a wine trade veteran and winery insider turned wine writer, who has advanced Israeli wines for 35 years. He is referred to as the English voice of Israeli wine and is the Wine Writer for the Jerusalem Post. www.adammontefiore.com