You need to be with someone with a lot of knowledge and have a good imagination to reveal the hidden secrets of the terrain. There I was with the famous archaeologist Professor Yuval Gadot, clamoring down the forested slops of Ramot Forest in the Judean Highlands, near the entrance to Jerusalem. He led the way with the enthusiasm of a child, supported with the deep knowledge of a professor, with decades of archaeological finds and ground breaking papers under his belt. Even though he knew what was coming, there was still some of that infectious boyish enthusiasm as though he was discovering everything for the first time.

This article first appeared in the Jerusalem Post.

Professor Gadot leads the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures at Tel Aviv University. He told me he was studying Humanities, went in to a lecture on Israel in the Iron Age and was hooked. He knew from that moment he would become an archaeologist. Since then, his fame has spread as the number of publications clearly illustrate. It was therefore a privilege for me to find myself on an informal hike with him. His knowledge, enthusiasm, curiosity and modesty were outstandingly apparent on the two occasions we met.

The ground was very stony, rocky and patches of solid stone were interspaced with pools of earth. The landscape was decorated with a forest of pine trees. The late winter flowers had started to show themselves, as if gingerly looking out of the window, to see if it was spring yet. He discovered in close proximity one wine press, then another and the ruins of a watchtower.

There is nowhere you can go in Israel without coming across ancient wine presses. I always get a frisson of excitement when I come across one, because I can envision someone making wine in ancient times, and when they are found near modern wineries and vineyards, the contrast between ancient and modern is particularly vivid. Hiking across the rough, hilly terrain, all the untrained eye will see is a flat limestone basin, cut into the rock. It is usually overrun with scrub, and you will often find nearby what looks like a random pile of large stones. It takes an archaeologist, historian or wine lover with a romantic imagination, to join the dots and fill in the gaps. Ancient wine presses in Hebrew, are prolific in the Judean Highlands and they provide a window into ancient times, giving an opportunity for us to visualize how wine was made in days gone by.

These wine presses, dug and hewn into rock, would more often than not be close by or actually within a vineyard for quality control and efficiency reasons. If the newly harvested grapes were too far from the press, there was a danger the weight of the grapes in the harvest collection baskets, would break the skins open, and the natural yeast on the grape skins would cause premature fermentation. The desired product was wine, not vinegar, so the press would most likely be in close proximity to the vineyard.

Isaiah’s Song of a Vineyard (Isaiah 5) says the following: “My loved one had a vineyard on a fertile hillside. He dug it up and cleared it of stones and planted it with the choicest vines. He built a watchtower in it and cut out a winepress as well.” We learn so much from this. The vineyard was on a slope for drainage and to catch the maximum rays of the sun. The “Gat” or wine press would be made up of a pressing floor, for stomping on the grapes and a deep pit, known as the “Yekev” or winery, where the fermentation would take place.

Most of the wine presses covering the Land of Israel date from Byzantine times, but there are areas of the Judean Highlands where they date back all the way to the Iron Age, which is approximately 2,600 years ago. Professor Gadot explained to me that the wine presses we saw at Ramot fell into the earlier period. When there are a number of wine presses in reasonably close proximity, they presumably serviced a number of different plots of vines. What we saw was not a wine complex of the size discovered in Yavne (c. 500 CE) – the largest Byzantine wineryever found, but also, they were not examples of domestic winemaking or a village community undertaking. Professor Gadot told me they were most likely part of the agricultural estates owned by a nobleman in Jerusalem. This indicates there was a highly specialized wine economy in what was then the Kingdom of Judea. Much of the agriculture in the surrounding hills was to

supply the Judeans and Jerusalem.

There is of course no evidence of vines left, and where I visited, there was clearly no room for the large rectangular vineyards of today. Their vines were instead planted in pockets of earth in the suitable places between trees and the solid rock formation, which could not be easily

penetrated. The vine is naturally a climber or crawler. Left to its own devices, it will climb trees or sprawl along the ground, or both. The vines were not trellised or laid out like manicured gardens as they are today. Part of the over growth may even have extended to the solid rock which would help reflect the heat of the sun to aid ripening of the fruit.

Most sites will display a pile of stones or rocks, seemingly there for no apparent reason. Here an archaeologist is necessary, to reveal the secrets. The land is too stony and rocky for many forms

of agriculture. The farmer even today will follow the maxim “if you can, plant fruit trees, but if the ground is inhospitable and nothing else will grow, plant vines or olive trees.” These stones were impediments that would have had to be removed from the earth to allow planting of the vines. Nothing would be left to waste. The stones would have been used to build a watchtower for a guard to watch over the precious vines. These may have also been used to provide shelter or been used as a rudimentary ancient tool shed. The remains of one of these towers, as described by Isaiah, would always be close to the wine press and vineyard. The same stones may have alternatively been used to build a dry-stone wall to demarcate ownership of a plot, or to build manmade terraces, particularly in the Judean Highlands.

The finished wines were put in animal skins or clay jugs known as amphorae. They would then be stored in nearby caves where it was cool and dark, before being distributed by donkey. In those days wine consumption was far greater than today. It was considered safer to drink than water, which was dangerous because it was a disease carrier. Wine was used to pay taxes – in the Judean Highlands area, particularly to the Assyrians. From the coastal area, it was traded and exported to Egypt and the Mediterranean basin. It was a mainstay of the economy. Wines

were not named after grape varieties or made from a blend of known varieties. Most were field or plot blends of whatever varieties happened to be in a particular place. The fetish for varieties is a modern development. The wines were instead named after the style of wine (strong, old young), the place it came from or the port from where it was exported (Gaza, Ashkelon, Carmel etc).

Wine was flavored in a similar way to a vermouth (with herbs and spices), or a Greek Retsina (with pine resin). The idea was that the flavoring would make the wine palatable, cover up all the wine faults and act as a preservative. Many of the additions were sweet, like date honey, but some were savory, like sea water, but on the question of additives, there was recently an extraordinary discovery.

Professor Gadot was one of the team excavating the City of David of Jerusalem. Is there another place on the planet more fraught and fascinating than this for the archaeologist? The dig took place in two locations. One was on the eastern slopes of the City of David hill, the other was in the Givati parking lot, west of the hill. This was where Gadot was working with colleagues. They found a lot of debris in the easternmost room of Building 101 – an administrative center in Iron Age Jerusalem. There were mere fragments of shattered clay jars, crushed and in some cases totally destroyed, by the Babylonians. A layman would have been distraught at the sight. For the

skilled archaeologist though, the excitement was just beginning. Some of these jars were painstakingly and incredibly rebuilt, shard by shard. The process of how they do this beggars belief. That they succeeded at all is testament to the patience and extraordinary talent of the

pottery restorers. These jars were found to have once stored olive oil or wine. When they discovered some of the jars had the stamp of a rosette seal, they realized the jars belonged to the Kingdom’s royal economy. They were dated from the time of King Zedekiah, King of Judah in

the 6 th century BCE.

Using the Organic Residue Analysis (utilizing new techniques) they made a sensational discovery. For the first time ever, after analysis of the residue of the wine jars, they found evidence ofvanilla. This rare, expensive and exotic luxury would have been imported from the east in the spice routes that crisscrossed the Negev. It would have then been used to flavor the wines of the Judean elite to take the edge off a rough wine. Lovers of an oaky Chardonnay will appreciate the sweet comforting aromas of vanilla that come from oak aging. It appears there is nothingnew under sun. It is easy to gloss over the painstaking work and the long time the whole archaeological process took in a few paragraphs, but their discovery made headlines around the world.

The Canaanites were in their time the world’s best winemakers. They influenced the Egyptians, the first great wine culture, and bequeathed their skills to the Phoenicians, who traded wine to the west, and also to the Israelites and Judeans. It was because of the importance of wine then, in this very place which we call home, that this exalted beverage became an integral part of Judeo-Christian religious ritual and a staple of western culture.

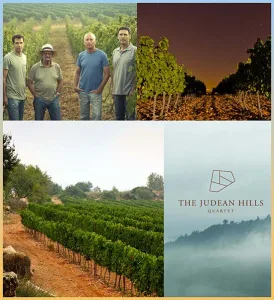

How exciting it was for me, with the guidance of Professor Gadot, to see evidence of a Judean wine press and then read his research about the wine preferences of the Judean elite. All this in an area we now call Judean Hills, today one of our finest and most buoyant wine growing

regions. It appears that there is nothing new under the sun. What was, is what will be…..and that is part of the magic of our unique wine story.

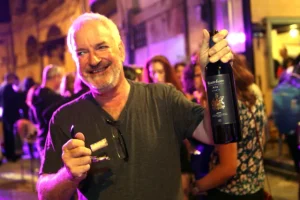

The writer is a wine industry insider turned wine writer, who has advanced Israeli wines for 35 years. He is referred to as the English voice of Israeli wine and is the Wine Writer of the Jerusalem Post. www.adammontefiore.com