One of the requirements to make a wine Kosher in Israel, is observance of the Shmittah year. Secular Jews and certainly everyone who is not Jewish, are endlessly confused about what this entails. The observance, ambiguities and contradictions of Shmittah defy rational explanation. This is my effort to write an explanation for the curious. Of course, it goes without saying, religious Jews, Torah observant Jews and Orthodox or Ultra-Orthodox Jews, should seek their explanations and discussions about the minutiae of the Halacha (Jewish law), from a Rabbi. This is not for them.

There is a law recorded in the Bible which states that every seventh year, the fields should be left fallow and allowed to rest. It is forbidden for a Jew to sow, plant, prune or harvest during the year. This is known in Hebrew as ‘Shmittah,’ meaning ‘release’. The last Shmittah years were 2001, 2008 and 2015. The quality of the vintage has no respect for Jewish law. 2008 was a wonderful vintage, yet 2015 was one of the worst.

The current year 2022, 5782 according to the Jewish calendar, is a Shmittah year. It is relevant only to produce grown in the Eretz Yisrael – the Land of Israel. Kosher wine produced in California and France does not have abide by the rules of the Shmittah year, but for Israeli wineries it is a seven year headache or mitzvah (commandment), according to your vantage point.

The custom of a ‘day of rest’ or a ‘year off’ was given to the world by the Jewish faith. Everyone is familiar with the ‘Sabbath’ and ‘Sabbatical year’ that result from this. From a moral point of view, the Shmittah year gives a strong message of social justice and egalitarianism. The concept of giving the land and its workers a one year sabbatical and reserving part of the harvest for the poor or for those disadvantaged, was a socially progressive idea in Biblical times. These practices address the profoundest issues of spirituality versus materialism.

Like most of the Jewish Biblical agricultural laws, it also makes good agricultural sense. Farmers have always implemented crop rotation or nitrogen cycles to put the goodness back into the soil. However adherence to this as far the Jewish religion is concerned, has become more symbolic due to economic realities. For instance, it is simply not viable to practice crop rotation when growing vines. A year without wine would cripple wineries and vineyard owners.

From their religious viewpoint, the Rabbis have had to come up with their own solutions. The flexibility stems from these economic concerns. Therefore a special dispensation is given to relieve farmers of this requirement and the land is symbolically sold to a non Jew for the duration of the seventh year. This is known as the ‘Heter Mehira’ (‘permission to sell’.)

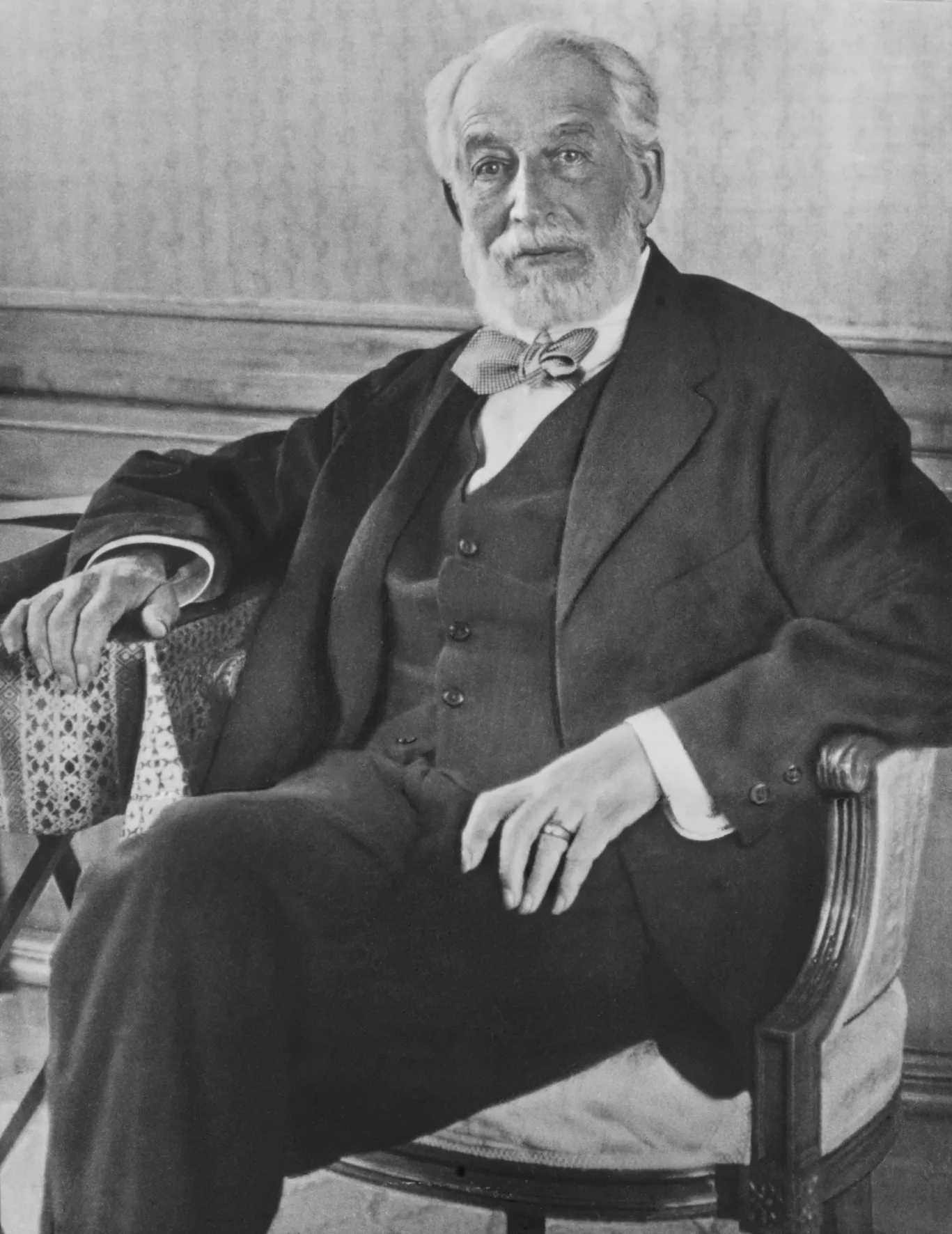

This creative solution was developed out of necessity some time ago. When Baron Edmond de Rothschild planted vineyards and supported the new Jewish farming villages of the late 19th century, he founded a wine industry in the Holy Land for the first time in 2,000 years. However, 1889 was a Shmittah year. Swiftly, battle lines were drawn up. On one side there were strictly religious Jews who chose to observe the Shmittah, exactly as written in the Bible. Their thinking was ‘we have waited 2,000 years to observe the agricultural laws in Eretz Yisrael. Nothing will stop us now, when we have waited so long.’ There were others, also religious, but more practical, who feared economic disaster if the Shmittah year was observed literally.

The debates and arguments were vehement, and nearly tore apart the fragile new farming communities and the pioneers of the First Aliyah. Out of necessity, Baron Edmond de Rothschild and his administrators backed a more lenient and flexible alternative. Eventually the Heter Mechira compromise was supported by a few key Rabbinical figures, enabling it to be implemented. The debates continue until today, but the arguments were never again as fierce as those of 1889.

An alternative to Heter Mechira, is to put the winery under the supervision of a Rabbinical board who are known as an Otzar Beit Din (‘storehouse managed by a Rabbinical Court.’) The Beit Din manages the people in the vineyard and winery for this particular year. This is part symbolic because the regular growers and winery staff are employed, but it gives a semblance of control allowing many Torah observant Jews flexibility to be able to enjoy an Israeli wine made in the Shmittah year.

Customs vary amongst Israeli wineries producing Kosher wines. For instance, Carmel, the historic winery of Israel, and Barkan-Segal, Israel’s largest winery, will both operate with a Heter Mechira in 2022. Yet, the Golan Heights Winery, the pioneering winery of Israel, will be under the auspices of an Otzar Beit Din. As for Zion Winery, Israel’s oldest family winery founded in 1848, they will not be making wine at all during the Shmittah year. Each and every winery decides according to its own wishes.

The produce from a Shmittah year is considered especially holy. It is regarded as ‘Kedushat Shevi’it’ (the holiness of the seventh). Therefore a Shmittah wine should not be taken out of Eretz Israel. Furthermore, if you open a bottle, you should be careful to consume it all and not throw it away. In America, the Kashrut authorities do not have to deal with the Shmittah conundrum, because it only is relevant to Israel. Therefore they can afford to be stricter. They are reluctant to sanction compromises for economic reasons.

A Torah observant Jew will prefer to drink an Otzar Beit Din wine, distrusting the Heter Mechira. Though, my feeling is that most wineries prefer the Heter Mechira. At the same time, a Progressive, Reform, Conservative, or secular Jew, will not feel bound by any restrictions. They will most likely feel free to drink any wine from this particular year.

From a wine point of view, the same winemaking practices apply in Shmittah year as every other year. The winemaker’s task is to make the best wine he can from this particular vintage and wine lovers, connoisseurs and wine professionals, will not notice anything different about the quality and style of the finished wine. The bottle will even look the same. The information a religious Jew needs to make his decision, is written in small lettering on the back label.

In the end, the policy is that everyone’s interests are looked after. The religious Jew, Rabbi, winemaker and vineyard owner are each loyal to their own beliefs and do enough to satisfy the other, without giving way on their core beliefs. However, in a Shmittah year wine is made, as in every year. Those bound by Jewish law will observe the restrictions. However the reality is that many Jews and Israelis do not feel bound by Jewish law. It is quite possible that they will not even pay attention to the fact the wine they are consuming is from a Smittah year.

So strictly observed by some, purely symbolic to others, it remains a classic example of a Jewish compromise whereby everyone follows their own truths. Still confused? No-one will attempt to say it is not confusing!

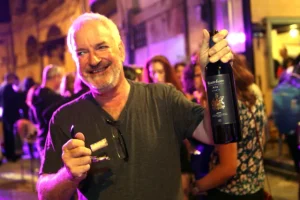

Adam Montefiore is a wine industry insider turned wine writer, who has advanced Israeli wine for 35 years. He is referred to as the English voice of Israeli wines and is the wine writer of the Jerusalem Post. www.adammontefiore.com