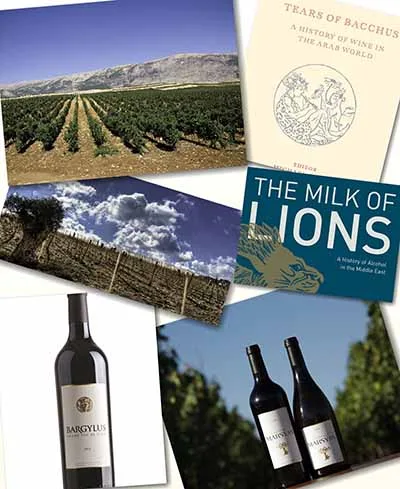

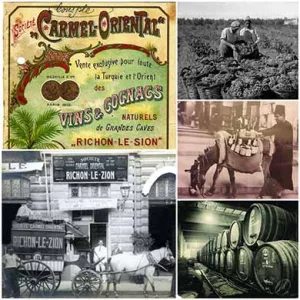

Wine in the Arab world sounds like a non sequitur, but it is not. Don’t forget the Phoenicians were the greatest wine traders the world has seen and they influenced the prominence of the Levant in the development of wine and wine culture. Furthermore, the Lebanese today make wonderful wine. Their most well-known winery, Chateau Musar, is more famous than any Israeli wine and the previous edition of the World Atlas of Wine made the point that a wine from Syria, Domaine Bargylus, was considered the best wine in the Eastern Med. Humbling if you believe Israeli wines are the only wines in the world! I was recently fortunate enough to read ‘Tears of Bacchus: A History of Wine in the Arab World’, by Michael Karam. Michael and I are mirror images. He is English Lebanese in a similar way that I am English Israeli. He is the world’s spokesman for Lebanese wines. When I contribute about Israeli wine to Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine Book, The World Wine Atlas and Jancis Robinson MW’s Oxford Companion To Wine, Michael Karam is at the same time telling these publications the story of Lebanese wine.

He has in the past written two books which I am proud to have in my library. ‘Wines of Lebanon’ and ‘Arak & Mezze’ are the literary standards for two of Lebanon’s greatest gifts, that of wines and arak. I grew to love Lebanese wine over thirty years ago when I first met Serge Hochar of Chateau Musar and organized a memorable vertical tasting of Musar wines in London. I then put Musar and Yarden wines together on the wine lists of over fifty restaurants of the hotel group where I was wine manager, under the heading ‘Eastern Mediterranean’. This was when my belief in the Eastern Mediterranean as a region was born and the beginning of an interest in Lebanese wine. Over the years I came to know Lebanese wine quite well including many of the winemakers, whom I met at wine exhibitions. I also got to know Michel de Bustros who founded his Kefraya winery during a war, and created Comte de M, the iconic wine of Lebanon, along with Musar. Sadly, neither he or Serge Hochar are with us anymore. More lately with the proliferation of new wineries, it has been difficult to keep in touch, but I have the utmost respect for the quality and variety of the Lebanese wine scene.

I have always thought the differences between the Lebanese and Israeli wine, make both narratives complimentary, and yet the short distances and similarities in terroir, mean we could learn a great deal from each other. Certainly, this small area of the Levant would comfortably fit into California. Whereas there is a chasm between both countries, the international consumer, sommelier and retailer see them together, leading a revival of this historical region.

Karam’s new book is a stonking good read. He has gathered together a distinguished list of contributors to tell the story from the beginning of wine until today. The book is absorbing, interesting and I read it from cover to cover. Hugh Johnson, the world’s most distinguished wine writer, wrote in the forward: “Michael Karam has succeeded in recruiting an intriguing bunch of writers…to bring this dramatic story to life with verve and passion and with a dollop of academic rigor thrown in.” He explains “the Middle East remains a turbulent, fascinating and intoxicating part of the world, but it also gave us the gift of wine.” The book leaps from Noah, the first vigneron, via the Canaanites, on to the Phoenicians, not forgetting the influential legacy of the Greeks and Romans, then to the important Christian monasteries, finally arriving in the Lebanon of the 19th century. It is a book I will return to again and again, dipping in to read world renowned experts like Patrick McGovern on the origins of wine, Alex Rowell on the wonderful Islamic wine poetry of Abu Niwas, Randall Hesketh on wine in the scriptures and the fascinating chapter on wine and Islam.

‘Tears of Bacchus’ was written after a discussion by Karam with the brothers Karim and Sandro Saadé. They are owners of Chateau Marsyas, one of the finest in the new wave of high quality Lebanese wineries. They are also owners of the admirable Domaine Bargylus. Marsyas is situated in the Bekaa Valley, the famous wine region of Lebanon, not so far from the magnificent Temple to Bacchus, at Baalbek. Bargylus comes from the hills above the northern Syrian port city of Latakia. Syria is fraught with well documented problems. Bargylus is a wine that is made with more obstacles than almost any other wine on the planet. The determination to overcome the nightmare and carnage in order to make wine, speaks volumes about the morals, determination and vision of the Saadé family.

Lebanon focused for years on the international varieties. Recently there has been an encouraging focus in both previously unfashionable ‘adopted varieties’ (as described by Karam), like Cinsault and indigenous varieties like Merwah and Obeideh. In the preface, Johnny Saadé writes that the proceeds of the book will go towards research into other local varieties. What a noble cause. It is almost worth purchasing the book for this reason alone. More similarities with Israel. We are also reviving our work horse varieties like Carignan and experimenting with local varieties.

The book is very relevant focusing on our region, but in modern times it reaches just Lebanon and Syria. I was hoping the book would also cover Jordanian, Palestinian and Moroccan wine to justify the mention of the ‘Arab world’ in the title. Maybe that will wait for the next edition.

Unfortunately, Palestinian wine is not that well known. It does not reach the attention maybe because of the buoyant success of Israeli and Lebanese wine, the mistaken assumption by many that Arabs don’t make wine because alcohol is forbidden for Muslims, and possibly the Palestinians themselves are do not succeed to get their wine story across. The political situation certainly does not help. There are many more important things than wine. The fact is that Palestinian Christians have made wine for millennia. During the time there was no industry as such, wine was made in the home, often by the mother in the family. It was a way of utilizing grapes the family grew. Some were used for food, others to make raisins or more likely to make dibs, a grape syrup. A proportion was made into wine, and this has occurred continuously throughout the long history of winemaking, even if under the radar. There is a current flowering of numerous Palestinian cookery books, which will hopefully encourage the curious to show more interest in their wines.

The monasteries Cremisan and Latroun have always proudly made Palestinian wine. Latroun is a Trappist Monastery founded in 1890 and Cremisan is a Salesian Monastery founded in 1895. Latroun made use of expertise from the France and were the first to bring varieties like Gewurztraminer and Pinot Noir to the Holy Land. I visited them for the first time recently. Cremisan took their expertise from Italy. Thankfully I have been able to follow the progress of Cremisan Winery over many years and I have had the pleasure of visiting them in Beit Jalla, not far from Bethlehem, a few times. This is the Holy Land’s most prominent Palestinian winery. Starting in 2007 the winery was refurbished and the great Italian winemaker, Riccardo Cotarella became involved as a consultant. Cremisan is the winery pioneering local, indigenous varieties like Dabouki, Hamdani (which we call Marawi), Jandali and Baladi Asmar.

Other Palestinian wineries include Taybeh Winery, near Ramallah, and the smaller Philokalia Winery from Bethlehem and Domaine Kassis from Birzeit. I thought a barrel sample of the Domaine Kassis red, a field blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot from their own family vineyards, was genuinely promising, and I loved their Dabouki from Hebron vineyards. The natural wines produced by Philokalia from old vine vineyards and indigenous varieties, are at the same time challenging, fascinating and wonderful. All these wines should be better known. Taybeh’s wines which I tasted once, were not that great, however I am not up to date. My efforts to try and taste their more recent wines have not yet proved successful. However, no doubt in terms of tourism, the owner’s investments which include a hotel, brewery and winery, are certainly praiseworthy.

In Israel we also have wineries owned by the Christian Arab community. We regard them as Israeli Arabs here, and they identify themselves also as Palestinian. There is Ashkar Winery in Kfar Yasif in the Western Galilee. It is an immaculate domestic winery which pays homage to Ikrit, to where the family dream of returning after being expelled for inexplicable reasons. Their Sauvignon Blanc is excellent and full of character. Jascala Winery based at Jish, overlooks their vineyard on the slopes of Mount Meron in the Upper Galilee. Their Merlot is always worth tasting and the Cabernet Franc is a rare treat. Then there is Mony Winery, situated at the Dir Raffat Monastery in the Judean Foothills, producing wines certified as kosher. This is a larger winery, representing great value for money. Their Colombard and Shiraz are my favorites.

The wines are gradually becoming better appreciated. Cremisan’s Hamdani Jandali white wine blend garnered attention of international wine critics, including Jancis Robinson MW, the most famous of them all, and Ashkar wines were listed by iconic chef, Yotam Ottolenghi. The elephant in the room is the underlying and ongoing political situation. My view is that a vine does not know if it is Israeli, Palestinian, part of disputed or undisputed territory. When I meet the winery owners, I see a winemaker, not a politician. Furthermore, when I taste their wines, I am sampling a wine that is made with passion and individuality, granted in a certain place. However, I find it hard to see a political statement in the taste of a wine.

Jordanian wine is unfortunately barely known outside Jordan. The Zumot family’s Saint George wines are organic and highly regarded by those that taste them. I also hope to taste them one day.

All these wineries remind us of the important heritage of Christian winemaking in the Eastern Mediterranean, Levant and Middle East. Certainly, they have a place in any history of the Arab wine world. However, their absence does not detract from the excellence of the book. ‘Tears of Bacchus’ is both absorbing and fascinating, and is thoroughly recommended.

If this is a book that interests you, then ‘Milk of Lions’ by Joseph El-Asmar is also well worth reading. It is a history of alcohol in the Middle East. Much of the subject matter is similar, but the information is presented differently. Believe me, I read ‘Tears of Bacchus’ in one day, and ‘Milk of Lions’ the next. I could not put either book down. The author beautifully covers the paradox of Islamic wine poetry, with examples from different eras. The main difference is that the focus is on alcohol, including wine, and after a broad journey through the ages, the story distills into an explanation of Arak Lebanese style. I know the Lebanese regard their arak with the same reverence that a Scotsman regards his whisky. Many winemakers I know are prouder, of their arak than their wines!

The book was inspired by the author’s decision to build a house in the middle of a vineyard close to Jezzine, in South Lebanon. His dream was not to produce wine, but to make a hand crafted arak. This led to a whole series of questions about the history of arak in particular and alcohol in general, and he was unable to find the information he sought. So, he decided to do his own research, and this very readable, informative book is the result. It is also highly recommended. Here too, we have Israeli Arab families making arak. Masada, with Lebanese expertise, and Kawar, with inspiration from Jordan, are two of the finest Israeli araks.

The Eastern Mediterranean is a wine region defined by war, strife and religion. Nowhere else in the wine world is religion such an issue, but Christians, Jews and Muslims all make wine here, as they did thousands of years ago. However, the ongoing disputes between Greece & Turkey, Israel & Lebanon, Israel & the Palestinians, and the Republic of Cyprus & Northern Cyprus, are real and underline all daily activity. I know. I once made the mistake of ordering a Turkish coffee in Cyprus! Maybe if we all drank less coffee and more wine, the region would become a calmer place.

Making wine is basically an investment in tomorrow. Planting a vineyard in lands of strife is a statement of hope. Michael Karam writes: “…the Arab wine industry….was born with early man, cultivated by the Phoenicians and celebrated in Baalbek by the cult of Bacchus. It can be found in monasteries and vineyards of Mount Lebanon and among the nation’s bubbling arak stills. It is a story, woven from threads of myth and reality, tying a glorious past to a hopeful present..””

I salute the winemakers of the Levant for their courage, bravery and optimism. Unfortunately, politics is a divide that can’t be breached at present, but wine is a brotherhood that extends above all. The Levant includes Lebanese, Syrian, Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian wine and it is a tragedy we can’t all meet to put the world to rights over a glass of wine. At least the wines should be able to meet on the shelves of wine shops and wine lists of restaurants, alongside the other Eastern Mediterranean wines, of Cyprus, Greece and Turkey. What is clear is that each individual country is making their best wine in over 2,000 years. Maybe Bacchus is no longer crying, but is viewing the renaissance of wine in the Levant and the Eastern Med with a joyful smile? Tears of Bacchus’ by Michael Karam, is published by Gilgamesh Publishing and costs £25. The Milk of Lions’ by Joseph El-Asmar, is published by Gilgamesh Publishing and costs £19.95.

Adam Montefiore is a wine industry veteran who has advanced Israeli wine for over thirty years. He is the wine writer of the Jerusalem Post. www.adammontefiore.com