Avi Feldstein, poet, philosopher, barman, grew up in Tel Aviv, from Romanian roots and read Literature and Philosophy at Tel Aviv University. He started as a tour guide. When I first came to Israel he was the bars expert specializing in spirits. The company he worked for, Segal, were then the main importers, bringing in brands like Martini, Jameson and Glenmorangie. By absorbing the material and immersing himself in the drinks world, he learnt enough to become the main expert in the country.

He acted as brand manager and spirit ambassador for the brands Segal imported, and was the main educator not only on product knowledge but also on how to be a professional barman. He also wrote for the Hadashot newspaper. Yet, with age, maturity and an expanding of horizons, Feldstein gradually moved from spirits and bars to vineyards and wine.

It is a known route. One of my sons was one of the best barman or mixologists in Israel. All the time I told him, that eventually he would get the wine bug because that world was seductive with even greater depth and more complexities. Sure enough, he is now working in wine. I too started elsewhere in the drinks business. I began my career in beer, studied wine & spirits and drifted into a career in wine.

Feldstein became development manager of Segal Wines and reached beyond his brief. Segal was a family firm. They were not the best winery of the day, but they were very innovative and pioneering with regard to importing wines and marketing. Their labels were the first in Israel to feature famous artists.

Feldstein with his new brief was restless. He was certain Segal could make better wines, if they controlled the fruit in the vineyards. However the winery at that time had a culture separating the vineyard and winery. Remember we are talking over twenty years ago. The feeling was ‘Let the vineyard grow its grapes and the winery make its wine. The vineyard manager and winemaker have different jobs. Let them get on with it.’

Avi Feldstein thought otherwise. With no scientific or viticultural background, without taking soil samples and data from weather stations, he decided the Upper Galilee was the place where Segal could make the great leap forward. He describes how when touring the prospective vineyard, he fell asleep under a tree. He woke up early evening and it was cold. He thought ‘eureka’, this is the place for a vineyard.

Now the Feldstein decision was not just based on an intuitive gut feeling. He had toured and interacted with the wineries Segal represented, which included icons such as Mondavi, Mouton Rothschild and Penfolds. He was curious, and absorbed information like a sponge. This gave him the confidence to challenge the existing order.

Zvi Segal, the patriarch of Segal Wines, was outraged, saying if Feldstein did not think the wines were good enough, then he could leave. Feldstein stood his ground and the vineyards were planted. The Dishon and Dovev vineyards were to define the new quality of Segal Wines.

A success story has many fathers, and many wineries were starting to think of new developments in the Upper Galilee, but Feldstein was amongst the very first. This started a trend of wineries situated in the center of the country planting vineyards in the Upper Galilee.

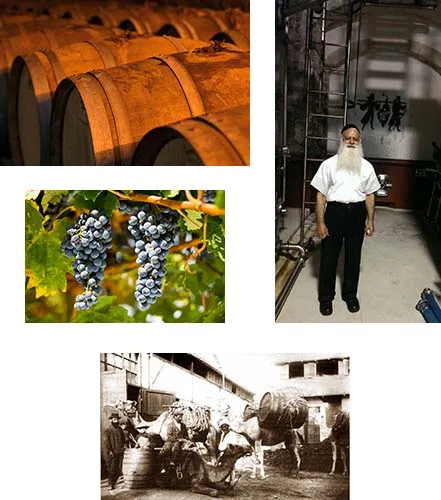

In the late 1990’s, Avi Feldstein followed this by becoming the winemaker. So the initiator of the vineyard, became the person to receive the grapes a few years later. He was totally self-taught, which is contrary to the more usual route of gaining winemaking qualifications. As Feldstein reminded me, it was not so long ago that people did not learn in universities, but took apprenticeships, studied in libraries and learned from on the job, practical experience.

It may not be politically correct to say it, but I believe the finest Segal wines were made by Avi Feldstein. They certainly were not at that level before he arrived.

There are four wines that I most associate with Feldstein. Firstly, the Segal Unfiltered Cabernet Sauvignon, which he took over and improved instantly. The quality and look of this wine was the first wine that showed the new quality of Segal, where the innovative presentation was matched by the quality of the wines. This is still the prestige wine of the company.

Then there were the single vineyard wines, from the Dishon and Dovev vineyards in the Upper Galilee. These are today branded Rechasim. The wines were planted, grown, nurtured and turned into quality wines by the same creative hands.

Finally there was the inexpensive, house wine of the company which was a simple wine with the words ‘Shel Segal’(Segal’s Wines) handwritten on a plain label. Another bit of marketing brilliance from Zvi Segal. When the company was bought by Barkan, even then the second largest winery in the country, the ‘Shel Segal’ Regular Red became one of the best selling wines in the country.

Feldstein is most associated with the Argaman grape, which was developed in the 1980’s and planted in the 1990’s. This was a cross between Carignan, the work horse grape of Israel and Souzoa, the Portuguese variety. The idea was to create a good blending grape, with excellent color.

In a master stroke, Feldstein planted it in his precious high altitude, Dovev vineyard. Previously Argaman had been uninspiring in the warmer coastal regions. The result was an impressive award winning wine, including a gold medal in France, and he justifiably received the nickname Mr. Argaman for his efforts.

Avi Feldstein is an instinctive winemaker with a touch of creative genius. He is not bound by any rule book and makes wine according to an educated gut feeling, gained from observation, listening and experimentation. He has a feel for the vines and an understanding of what is needed to turn the humble grapes into quality wine.

For instance, when he made his famous Argaman, he decided to ferment it over the skins of Merlot grapes in order to provide extra tannins. Currently, he is still experimenting with Argaman, drying the grapes in order to provide more concentration of flavor. He is also making a Dabouki, a genuine indigenous white variety. The wine is in stainless steel, but stored on its lees where he practices bâtonnage (stirring the dead yeasts periodically) to enhance complexity. None of these techniques are original, but he knows how to adapt and implement them to suit his needs.

He has now left the Barkan Segal empire and is concentrating on his own small, handcrafted boutique winery. Why bother making Argaman and Dabouki? Because it challenges him and he would get bored if things were too easy. He also works with Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah, along with the more usual classic varieties. He receives grapes from the Zichron Ya’acov area, Gush Etzion and the Upper Galilee in his temporary winery set up in an agricultural facility near Hod Hasharon.

These wines are worth watching out for. They will be good quality, original and without doubt every decision will explained by a personal story, and anyway, where else will you taste a quality Argaman and an Israeli made Dabouki?

Many chefs make follow exact recipes whilst others will adapt according to the best ingredients of the day. Some barman are slaves to the old recipe books for named cocktails, whilst the new mixologist makes it up as he goes along, taking into account the customer’s wishes and what he has around him. There are winemakers who play safe, making wine by numbers, and those like Avi that add a personal twist. Let’s call it creative individuality.

What is the difference between Avi Feldstein the mass market winemaker producing hundreds of thousands of bottles for Segal and the Avi Feldstein making a few thousand bottles in his own miniscule winery? He has a great answer: ‘Feldstein Unfiltered!’ That is exactly what I want to see. Handcrafted wines, with a sense of place and the thumbprint of an individual. This is why I will be seeking out his wines with great interest.