This article first appeared in the Wine Talk column in the Weekend Supplement of the Jerusalem Post

I was so sorry to hear of the untimely death of Serge Hochar, a true cedar of Lebanon. He was one of wines most original and much loved personalities, which was expressed through a unique wine, Chateau Musar.

The winery was founded in 1930 by Gaston Hochar, Serge’s father. He planted vineyards in the Bekaa Valley, a current stronghold of the Hezbollah, where all the best Lebanese vineyards are situated, but kept the winery at Ghazir, in a safer Maronite Christian area. (The Hochars are Maronite Christians.) A major early influence was Ronald Barton of the Bordeaux Chateaux, Langoa Barton and Léoville Barton. Gaston’s second son was named Ronald in his memory.

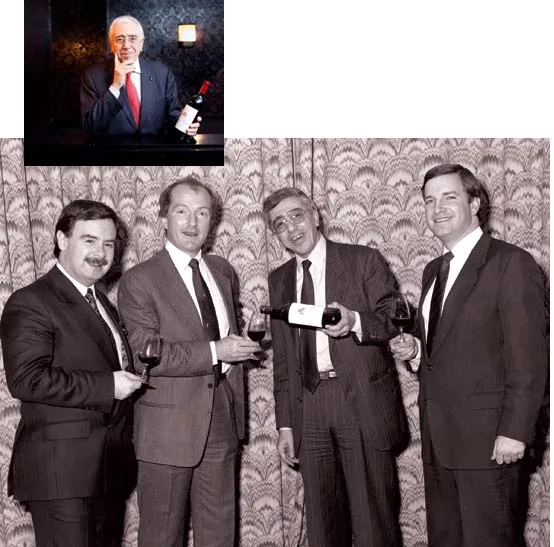

Serge Hochar was born in 1939, and studied in Bordeaux. When the Civil War struck Lebanon, he took his wine around the world to find new markets. He was an elegant, charming figure, in a pin stripe suit, with all the exaggerated hand movements to support his French accented English. It was the mischievous twinkle in his eye, gap-toothed smile and wonderfully expressive eyebrows that caught your attention.

He was a wine philosopher who would answer the most basic question with his own question, like querying the reason for being and wines place in the universe. “I know nothing about wine” he once said, “and each day I discover I know less.”

In 1979 Chateau Musar was ‘discovered’ at a wine fair in England and since then took its place as one of the world’s most idiosyncratic, recognizable wines. He brought Lebanese wine to the attention of the world and made his Chateau Musar the icon wine of the Eastern Mediterranean. On many occasions it was the only wine outside the traditional wine producing countries on a Michelin star restaurant wine list.

Chateau Musar is a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cinsault and Carignan. Part classic Bordeaux, part spicy Rhone. It is a wine that does not see a customer until at least seven years after the harvest. To put this into perspective, the current releases of the Margalit and Castel wineries are from the 2012 vintage.

The Musar red is a unique expression of the Hochar laisser-faire mode of winemaking. Many look at its tawny hue and nose the volatile aromas and insist the wine is faulty, oxidized and past its best. Others are in rapture at the exotic character with a combination of aromas of ripe plums, sweet dried fruits, spice along with the heat of the Lebanese sun. It is a wine that appears tired in its youth and gains a second wind and extra layers of complexity as it ages.

The enigmatic Musar white is even more unconventional. It is a blend of two indigenous Lebanese varieties, Obeideh and Merweh. Again, the purist would say it was flabby, lacking up front fruit and acidity. The patient Musarophile, prepared to wait up to 20 years, would find a white wine with honeyed aromas, whiffs of honeysuckle and a touch of apricot, not a refreshing dry white wine, but a complex full bodied mouth filling wine without a beginning or an end.

Wine today reeks of sameness. Wines from Napa, Barossa and the Galilee begin to taste the same because of globalization and the advance in technology. The need to make wines over ripe and extra clean, strips them of personality. Musar is the ultimate expression of individuality, originality with a distinct sense of place. Whether the wines are your cup of tea is less important than the non-conformist approach which has to be celebrated.

Why would an Israeli newspaper be interested in a Lebanese winemaker The answer is because wine is above politics (something Serge used to say and he would know). I believe someone who truly wants to understand Israeli wine, should study our neighbors. Israelis have a self confidence that sometimes over talks itself. In wine too, not just football.

Well we have a great deal to learn from our neighbors, whether Cyprus, Greece, Turkey …or Lebanon. Never forget that if Chateau Musar is the most famous wine from our region, the World Atlas of Wine pinpoints the best wine from our region as being Domaine Bargylus…from Syria! I spend my life championing Israeli wines of which I am very proud, but it is not a crime to be humble, reflective and to occasionally look sideways.

Like it or not, our wine growing region is the Eastern Mediterranean, not something called ‘kosher’. The best wines of Israel should be alongside the best wines of Cyprus, Greece, Lebanon and Turkey on the restaurant wine list and on the shelves of wine stores.

Serge Hochar was the charismatic figure who inspired a boom in Lebanese wineries. Twenty five years ago there were just five Lebanese wineries. Now there are fifty. It is still Chateau Musar that garners the most attention, but other Lebanon wineries are making wonderful wines today.

How I wish Israeli wineries would work together like Wines of Lebanon, or even Wines of Turkey for that matter, to advance brand Israel. I wish we had someone half as charismatic as Serge to lead the charge. Serge Hochar showed it was possible to break through the stuffiness and preconceived ideas of a conservative wine world.

I first came across him in the mid 1980’s. I was buying wine for Crest Hotels (part of the Bass Hotels Group) and put his wine on the wine lists throughout the chain, alongside an Israeli wine, under the heading Eastern Mediterranean. Thus was born my interest in the Eastern Med as a region.

I then organized and hosted a memorable vertical tasting of Chateau Musar in London in 1989. Hochar did not forget this. Years later when I

changed my status from an English buyer to an Israeli representing Israel at wine exhibitions, he was no less charming and kind and always gracious enough to refer back to ‘that’ tasting.

He broke out of the comfort zones of the ethnic market, where sales were easy, into the real wine world. He showed the way for wines in our region. If a Lebanese wine could break through the glass ceiling, there was a chance that Israeli wines could do so too.

He was a symbol of continuing life as normal through war and adversity. Hell, we can admire that quality here in Israel. In fact he did not make wine in 1976 and 1984 because of what we call in Israel, ’the situation’, but in other years, nothing would stop him.

I loved the way he makes his own wine in his own style. In a world of globalization and technical perfection, Hochar not only insisted on doing things in an eccentric way, he positively delighted in being different.

I found a meaningful quote by Serge in a wonderful article by Elizabeth Gilbert: “If you are open to understanding change, ..wine can teach you a lesson of tolerance. When you understand that all the flavors and smells and memories .. experienced over ……hours.. .. come from the same wine, then you will learn not to condemn any wine until you have stayed with it through all its stages.’

The essence of time, against the need for instant gratification. We taste wine and demand an instant description. If you like, a snapshot of the particular second it was tasted, provoking a knee jerk reaction from the rushed taster.

I remember seeing the great Michael Broadbent tasting wine with a stopwatch by his side and adding a tasting note every half an hour to capture the ever evolving wine. I think of Mark Squires the Israel expert in Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate team, who often takes the time to taste wine over a two day period.

Hochar understood that wine was an evolving thing which needs time to develop both in the barrel and bottle and even in the glass. It is not something to be summarized in a sniff or shluk (Israeli slang for a taste.) A great lesson for all wine lovers.

The Psalms say ‘The righteous shall grow like a Cedar of Lebanon.’ I feel privileged to have met him. Thank you, Serge, for the memories and the inspiration. This cedar has fallen, but Musar continues.

Adam Montefiore works for Carmel Winery and regularly writes about wine for both Israeli

and international publications.

[email protected]<span style=”vertical-align: bottom;”> (http://[email protected])</span>